A much-maligned fat makes a comeback

By Peter Burrows

As told to edible South Shore & South Coast

Q: We’ve been trained all our lives to say, “Eww, lard.” What’s changed?

A: The last few generations of Americans have been led to believe that eating pork lard leads to “clogged” arteries, heart attacks, and strokes. Lard’s reputation was especially maligned after World War II, as the industrial food complex promoted its highly processed, globally-sourced products—vegetable and other oils, margarine, and solid shortening—at the expense of animal fats. New discoveries about fat and nutrition are now revealing the healthy role lard played in our ancestors’ diets.

Q: Okay, then, what’s the latest nutritional information?

A: Lard from pastured pigs is classified as a monounsaturated fat, just like olive oil. Recent studies that have shown that eating foods rich in monounsaturated fats improves blood cholesterol levels, which can decrease the risk of heart disease. Monounsaturated fats in the diet may benefit insulin levels and blood sugar control, which can be especially helpful to control type-2 diabetes.

Lard from pasture-raised pigs is the second-highest food source of vitamin D (after cod liver oil), with one tablespoon containing 1000 IU. Because it is fat-soluble, vitamin D requires fatty acids—including saturated fatty acids—to be absorbed and utilized in the body. Unlike many margarines and vegetable shortenings, lard contains no trans fat.

Q: How does pasturing produce better lard?

A: Pigs must have access to sunlight to synthesize vitamin D and store it in their fatty tissues. Animals kept indoors, as in commercial hog raising operations, have no exposure to sunlight.

Heritage breed pigs—selected by many pasture-farmers—retain traits that allow them to thrive outdoors in most seasons. Darker hair and skin protects the heritage pigs from sunburn in summer, and cold weather stimulates them to put on thicker back fat—a main source of lard.

Q: Who were the first customers to start asking you for lard?

A: Professional chefs; they love lard for its fine cooking qualities. Its high smoke point makes it ideal for high-temperature cooking like frying. In baking, lard doesn’t melt as quickly as butter, so it allows for lighter, delectable crusts and breads. When it comes to pastry making, swapping in lard for some of the butter in a recipe increases the coveted flaky quality, while maintaining delicious flavor.

Q: Has the interest in lard spread to consumers who source their food direct from the farm?

A: Yes. The first consumers asking us for lard were passionate home cooks following the advice of food bloggers, writers, and chefs. However, lately we have been meeting folks who are concerned about healthy eating, asking us for lard they can render themselves. These farmers’ market conversations about lard can be quite spirited and entertaining, as we’ve been learning more about our customers, their interests in different styles of cooking, and personal preferences.

Q: What do your customers tell you?

A: One woman told us a touching story of being unable to make a pie as good as her grandmother’s, until the secret ingredient (lard, of course) was disclosed. Grass-fed beef lovers tell us they rub pork lard on roasts to help keep the leaner meat moist; they rave about how any vegetables added to the roasting pan come out caramelized and delicious. Devotees of confit (the ancient southwestern French method of cooking and preserving meats) require oodles of pure fat, and stir-fry aficionados know that lard’s high smoke-point makes it a natural in the wok. We also have a loyal group of hunters that ask for pork lard or ground pork to add flavor and moisture to their venison sausage.

Q: What part of the pig does lard come from?

A: There are three sources of lard from a pig. The best—leaf lard—comes from the “flare”, a visceral fat deposit around the kidneys and inside the loin. Leaf lard is pure white, and has little pork flavor, making it ideal for use in pastry. Fatback is the hard subcutaneous fat between the back skin and the muscle of the pig. It’s usually sold as flat, square blocks about an inch thick. Pigs also have a soft caul fat surrounding digestive organs, such as the small intestines. This membranous fat is used to wrap lean meats when roasting, or in the making of pates.

Q: Is rendering lard at home hard to do?

A: Rendering lard is easy, as long as you allow yourself the time and space to tackle the project. Essentially, the fat must be chopped or ground, and then slowly heated to melt the pure fat away from everything else. (There is a wealth of sources, both online and in print, to learn the nitty-gritty details.) The end result is a goldmine of jars of fat that can be kept frozen for months. And if you start with fatback, you also get a heap of delicious cracklings, the crunchy bits that are left in the strainer when the hot fat is poured off.

Q: What about buying lard ready-made?

A: Unfortunately, grocery store lard—when you can find it—is likely to have been hydrogenated to lengthen shelf-life, making it a source of trans fats. Industrial lard processing also commonly includes bleaching and deodorizing agents, emulsifiers, and antioxidants.

Perhaps the resurgence of interest in minimally-processed lard made from pastured animals will spark a revival in marketing a quality product, even at the supermarket. Until that day, we recommend you look to buy lard from farms where the animals were pasture raised. Talk to your farmer or your butcher to learn where your meat comes from.

Marshfield’s Peter Burrows is the owner of the former Brown Boar Farm, a Vermont-based, family-owned business offering restaurants and discriminating consumers humanely-raised heritage pork at affordable prices.

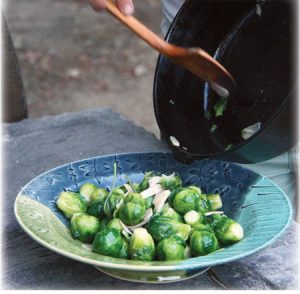

Brussels Sprouts with Sage and Garlic

- 1 pound Brussels sprouts, trimmed

- kosher or sea salt

- 2 tablespoons lard

- 1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

- 3 cloves garlic, peeled and sliced thinly

- 8-10 fresh sage leaves

- freshly ground black pepper

- 2 tablespoons port or sherry

Bring a well-salted medium potful of water to boil. Toss in the sprouts and cook until almost done—4 to 6 minutes, depending on size and density. Drain in a colander.

In a large frying pan, heat the lard and oil together until the fat is a bit shimmery. Add the sage leaves and fry on both sided until frizzled—a few seconds. Remove to a plate. Quickly do the same drill with the garlic—remove it also to the plate without letting it burn in the least. Shake the last water off the sprouts and add them to the fat tossing them about until nice and glossy. Grind over plenty of black pepper. Add the wine, and toss again. Turn out into a serving bowl, top with the sage and garlic, and perhaps a sprinkle of salt, and serve.

Serves 4.

~PM