by Pamela Denholm.

Seasons are marked by melting snow, migrating crows, and the farming calendar: a time to sow, a time to reap, a time to rest. Farming is age-old, it’s of lastingness, continuance, endurance, sameness, and change.

Small family farms dotted across the landscape of southeastern Massachusetts bear the greatest testament to this. In these fields, we see old timers’ tips and tricks, technology, and innovation woven in a seamless tapestry, a tapestry that tells stories. So what story does it tell of the last decade.

Community Supported Farming: The (R)evolution.

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) was a concept introduced on a single farm in Massachusetts in 1986. It was designed to bring consumers and producers closer together and give farms a cash injection early in the season in exchange for a share of the harvest later in the season. It was a revolutionary idea for consumers in that it removed consumer choice. Participating in a CSA meant relinquishing our grocery store mindsets in exchange for mindful spending and regional, seasonal, harvest-driven eating. Around 2006, the idea accelerated into mainstream popularity and by 2008, at the same time edible South Shore magazine was launched, just about every farm on the South Shore was starting to offer it. Fast forward to today: how has the concept evolved?

For starters, going from zero to hero was a big ask of consumers. In the produce section of a grocery store, we have the world at our fingertips, quite literally. It’s a system that fosters a culture of consumer choice and convenience. That’s a lot to give up for bunches and bunches of kale, beets, and turnips. Whilst many consumers crave the authenticity, ideals, and transparency of supporting local farms, some of us fall short on CSA integration in our own kitchens. It requires planning, creativity, and–dare I say it–finding time to cook! It requires the opposite of convenience; it takes effort.

To keep consumers engaged in the CSA concept, many farmers have evolved from a traditional weekly share of the harvest to a more flexible, pre-determined farm credit. This allows consumers to both invest in local farms at the beginning of the season, maintaining the authenticity and transparency of a CSA, but retain some control over what they get and when they get it. But is this a win-win solution? Farmers benefit from consumer commitment, though it’s much more difficult for them to anticipate consumer needs. It’s also riskier, and there is more waste. A noble concept designed to bring people closer to how food is grown, and have them share the experience (and risk) of crop successes and failures, is being adapted to meet mainstream consumers’ grocery store mindsets in which they carry very little risk, can feast on generous displays, shop any time, and choose anything.

What other farm developments have we seen?

The more ideas we share, the more we have.

Technology has had a substantial impact on agriculture. On a broad scale, we have genetically modified food crops, pesticide delivering drones, GPS guided tractors, and sophisticated weather and soil quality equipment. But it’s on the small farms where the impact of technology on farming methods and systems is the most interesting. It comes down to a simple idea: information sharing.

Farmers are tinkerers by nature. In just this decade, websites like Farm Hack and Open Source Ecology have allowed farmers around the world to collaborate, share ideas, and results. From bicycle powered seed thrashers to seedling transplanters, farmers can find inexpensive micro-machinery answers to challenges that, traditionally, had required big equipment (and even bigger price tag) solutions. These sites allow farmers to solve problems for other farmers, creating collaborative communities that have clicked over to social media pages.

Social media has had a giant and growing presence in all our lives. Most of us groan and roll our eyes and talk about the time wasted venturing down the Facebook rabbit hole or how, as a society, we are more connected but less connected. If there was a case to be made for the positive impact of social media, here it is. Social media has given consumers unprecedented access to farmers. If our goals with local regional food systems are authenticity and transparency, well then social networks are the delivery vehicle. We now have real-time information about what is happening in the fields. We know what’s growing, if it’s raining, what pests are plaguing our farmers, and what is being picked for the farm stand. Farmers can have satisfying one-to-many relationships with consumers through beautiful photographs, brief headlines, and post engagements. Marketing is not the only advantage: farmers belong to farm groups and can share real-time information about crop diseases, pest pressures, and crop successes and failures. They can share best practices and buy and sell both equipment and produce. In return, they receive in-the-moment responses from other farmers about what’s working on nearby farms. Gone are the days where farmers used to connect with each other once a year at a winter conference to download an entire season’s worth of wins and fails, and it has nurtured a growing inter-farm collaborative community.

So, the climate is changing then?

One of the things farmers are always talking about is the weather. In just ten years, farmers have seen weather patterns shift, a prospect which makes growing food outdoors seem even riskier. Falls are milder and lasting longer… but when the cold comes, it’s razor sharp. Summers are drier with longer spells between rainfalls, but rainfall events are heavier with several inches of rain falling in just a few hours. The mini-drought-miniflood series is becoming all too familiar, weakening crops and making them more susceptible to disease and pest pressures. Storms, ever stronger and more violent, move up the coast, dragging crop pests along with them. And shifting seasons means pests hang around later into the season.

To counter our changing climate, farmers are having to invest more in irrigation to become water-wiser and less reliant on surface water, which means drilling more wells. They also have to cover crop more intensely to prevent soil erosion as well as to improve soil nutrition so that crops are healthier and more resilient. These improvements help farmers maintain the status quo and keep them farming; however, the extra effort is not rewarded with extra yield, so farmers are being more strategic about what they grow while keeping consumers in mind.

The rise and fall of kale.

Kale rose to fame with the t-shirt slogan “eat more kale.” Once it was crowned a superfood, consumers just couldn’t get enough. Kale was showing up in quiches, pasta dishes, smoothies… even ice-pops. But, as with all superfoods, fame is fleeting and kale is now considered to be a mainstream vegetable. Before kale, it was almonds (almond milk, almond flour, almond snacks anyone?) Since kale, it has been avocados—I’m talking about you, avocado toast! Almonds are not locally grown, nor are avocados, so is there a locally grown, nutrition powerhouse set to rise to superhero famedom?

Farmers say that since the introduction of CSAs, consumers have become more adventurous. Staples like lettuce, tomato, cucumbers, and potatoes still get most of the attention at farm stands. But consumers hover over laden harvest baskets in search of that standout special something. We may not want to bring kohlrabi home every week, or fennel for that matter, but that doesn’t mean we don’t want to brighten our dinner plates with something interesting once in a while. Still, if there is anyone ingredient gaining momentum with trend-setting chefs, it has to be microgreens. Microgreens can be grown year-round, but it is their designer flavor profiles—spicy, sweet, or fragrant—and not necessarily their reliability that is winning them favor. With blends of brassicas, mustards, and herbs, there are no limits to our culinary creativity and microgreen flavor pairings. Jazz fingers, please.

Where to get some.

This has been an interesting decade for farmers’ markets. Every town wanted one. Every town had one. And then we had so many markets we ran out of farmers. Ten years on, we have fewer farmers’ markets, but they are of good sizes and filled with both new and familiar faces. Their offerings have expanded, and there are usually multiple produce farmers with a range of fresh fruits and field crops (and microgreens); everyone has their specialty, after all. Farmers also offer chicken, beef, eggs, lamb, and even goat products. Local fisheries are on hand alongside artisans selling dog biscuits or hand-poured candles. Prepared food vendors entice market-goers with fresh sandwiches and just-squeezed juices, and it’s not unusual to see shoppers amble around the market enjoying tamales, with a few extras tucked into their canvas market bags for dinner. Local musicians, activities for the kids, and food and garden lectures all speak to a market environment that has grown from a drop-in for fresh corn to a destination for the whole family. Just in case you can’t join the fun, many markets now also have online ordering and delivery services.

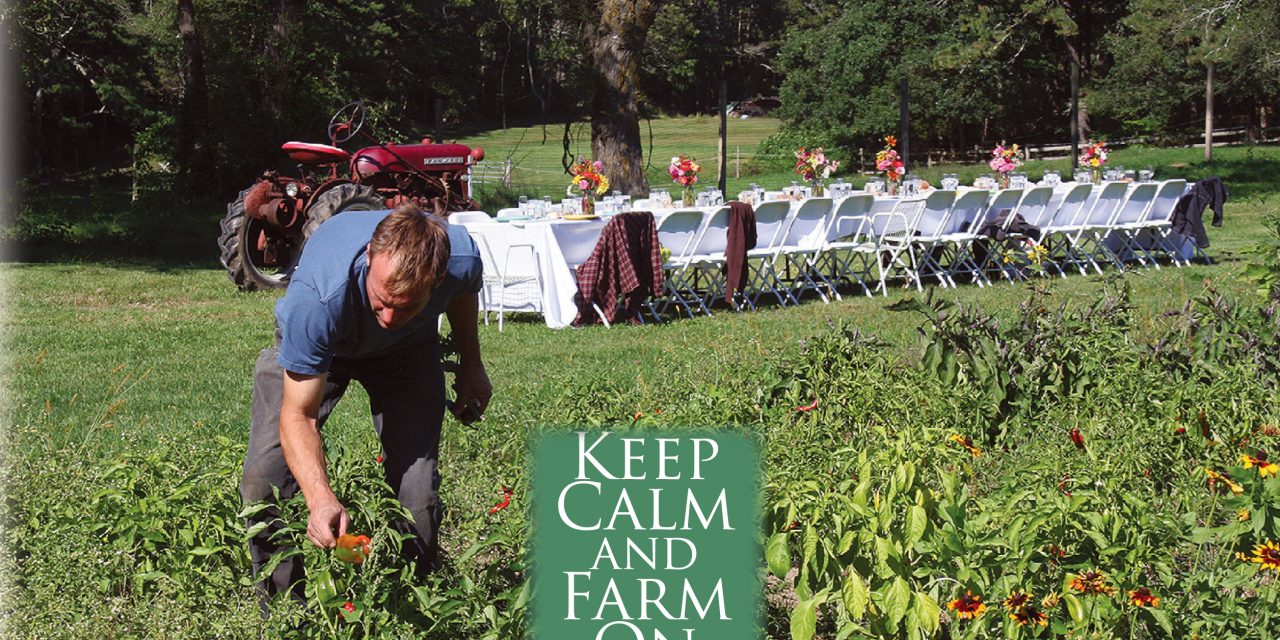

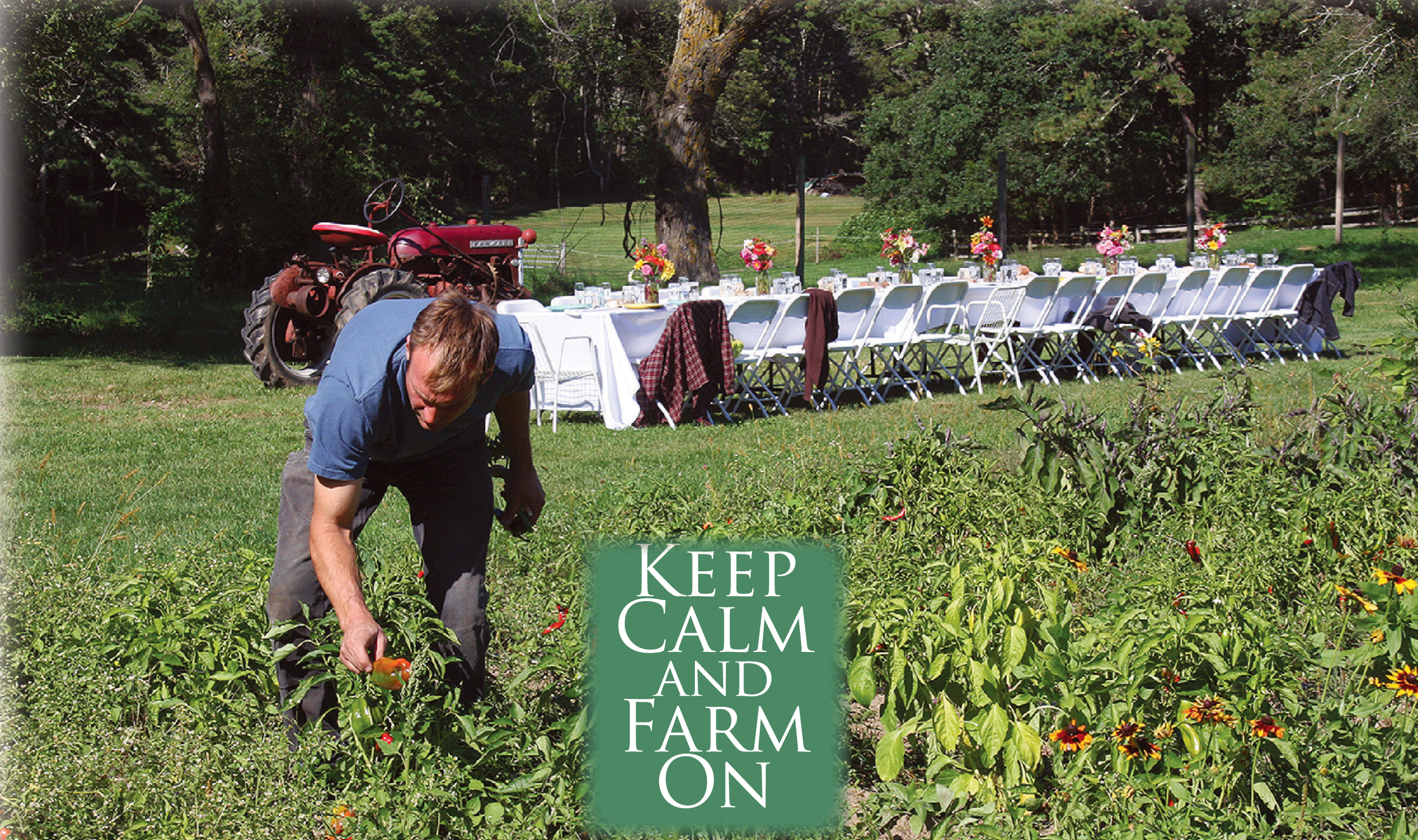

The lay of the land has changed over the past ten years, but not in a way that is immediately obvious. Fields might be a bit drier because of the weather, or a bit wetter, and crop choices have changed to reflect the altered pattern and changing consumer preference. The red barns are the same as they have always been, but they might sport shiny-mirrored solar panels. Corn mazes, cannons, and pick-your-own fields, as well as hay rides and cider donuts, are an ever-expanding kind of “farmtertainment” as suburbs build up around farms, and families look to farms to provide a rural agricultural experience. The local food movement has had more ups than downs and has given rise to a new generation of farmers passionate about sustainability, land stewardship, and growing good food.

The sun still rises early in the summer and, as they have done for centuries, the farmers with it, but today they have more resources at their disposal to face an ever-changing future.

Pamela Denholm has been an integral part of the local food landscape in the last decade. She hung up her crown as Queen of the Turnips for a new role as humble servant to those in need, but remains committed to the idea of healthy, vibrant, regional food systems centered around our farms.