Words and photos by Laura Killingbeck.

If you’re looking for Geoff Kinder, you can usually find him somewhere on the farm, moving piles: piles of hay, piles of fencing, piles of manure. Much of the work of raising animals on pasture is simply, efficiently, moving things around.

Paradox: something that seems to be contradictory but is also true.

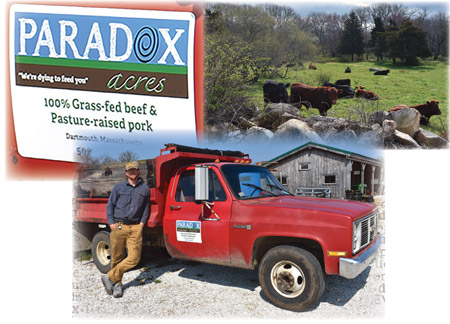

Geoff runs an independent meat agribusiness at a nonprofit working farm and education center called Round the Bend Farm, A Center for Restorative Community, in Dartmouth, Massachusetts. The farm has been home to various agripreneurs of which Geoff is one. For many years Geoff referred to his business as Kinder Meats. This made sense because his last name is Kinder. It was also a pretty good name for a business whose mission is healthy, well-treated cows, pigs, goats, and sheep, raised on healthy, well-treated land. In an era where most meat animals in the United States are raised on factory farms, the name felt relevant from many angles. Small-scale farming with a focus on holistic land management and animal well-being is, in human parlance, kinder.

But although the name Kinder Meats spoke an important truth, it also left out something equally true: that all those healthy animals, well-treated and raised on real pasture though they are, ultimately have to die. After all, we don’t eat them alive—hamburger is dead flesh. Genuinely caring for the well-being of animals we later kill to eat is one of the most persistent paradoxes of eating locally-raised meat. So when it came time to file an official business name, Geoff chose something even more expressive. His logo now reads Paradox Acres. The tagline: We’re Dying to Feed You.

PARADOX ACRES

Cattle in the Field at Round The Bend Farm

Now, this is probably a good time to mention that in conjunction with raising pasture-fed animals “kindly,” Geoff has a deep fascination with what he refers to as “blunt reality.” And in modern American culture, reminding people that the pork in their breakfast sausage was previously a live pig hits them with this bit of bluntness. Even though we understand that animal death is a part of eating meat, we’d rather not say so out loud in pleasant company.

This was not Geoff’s only message in the new business name. In fact, there were so many paradoxes tied up in the business of eating meat that one day we made a long list on a chalkboard: local meat is more expensive, but it uses fewer resources to produce and transport; many people think killing animals is cruel, but they’re happy to pay someone else to do it; commodity foods are cheaper, but partially because we pre-pay in taxes that subsidize agribusiness; you may be able to earn more money selling your land right now, rather than farming it for a lifetime. The list of paradoxes for how this whole food thing works goes on and on. And it’s not just about meat—the realm of paradox for veganism and vegetarianism is equally confounding. Any human diet made from food grown on a global economic scale probably doesn’t make much sense on a global ecological scale.

One of the central paradoxes of healthy meat production is this relationship between global economics and ecologically sustainable farming. Land is very expensive (especially in southeastern Massachusetts!), and sustainably managed livestock requires a relatively large amount of land. So in order to farm animals, you need to have access to a certain amount of wealth to buy and maintain that land. However, the meat you produce and sell has to fit into a marketplace where the value of meat is strangely low. Factory farms condense animals onto smaller amounts of land, which floods the market with a lower price point for meat. This tends to produce sicker animals and higher environmental consequences. So in many areas, one of the biggest paradoxes of sustainable farming is that you need a lot of land and wealth to produce a food that people expect to be cheap.

Round the Bend Farm explores this issue by providing farmers and educators with access to land that they otherwise would not be able to afford. In exchange, farmers and educators are challenged to find innovative ways to participate in positive ecological relationships and work holistically. Paradox Acres cows help maintain open spaces and endangered bird habitat through grazing; goats and pigs remove invasive species; pigs till soil to prep garden beds and make compost; and chickens take care of some pest control and weeding. All of these processes also become part of Round the Bend’s educational curriculum and programming.

It’s not easy to engage in work and a lifestyle that are both economically and ecologically sustainable—our current globalized markets are not designed for ecological balance. For farmers, activists, and anyone seeking to transform our communities in ecologically positive ways, this can be a frustrating conundrum. How do we extract ourselves from the paradoxes that inherently link our social systems, and still earn a livelihood? For Round the Bend Farm, the union of many different types of people from different social, personal, and economic backgrounds, challenging themselves to think creatively about sustainability, have produced some unique systems and circumstances where farmers are free to explore that issue. It doesn’t solve all the problems or unravel all the paradoxes. But it does allow us to confront issues directly, and create ways of living and working that hopefully move us in the direction we want to go in—towards an increasingly healthy, happy, and vibrant version of blunt reality.

For most people who consider buying Paradox Acres meats, the idea that they are consuming dead bodies is pretty disconcerting. (When I told Geoff that, he looked downcast, so I’d like to include here that the meat is really good, and people still love eating it.) And realistically, death is part of the reality of food, no matter how you label it. It’s just the truth. And when we consider the ubiquity of that truth, that’s when it seems like the depth of the paradox may be more about ourselves and our perceptions rather than anything else. Sometimes we humans tend to deny and ignore the most obvious things about our own lives.

What realities are we willing to face, and when we face them, what do we do with that experience and understanding? The world we live in may never actually make sense. Looking at the realities of our lives and social systems requires a certain radical acknowledgment of extreme and sometimes bewildering strangeness. It means allowing ourselves to feel troubled, and also hopeful, and keep moving forward. And sometimes, it means continuing, every day, to move piles.

Paradox Acres

Round the Bend Farm

92 Allen Neck Road

Dartmouth, MA 02748

(508) 938-5127

www.RoundTheBendFarm.org/agripreneurs/meat

Laura Killingbeck has been working with farm education centers since 2009. Her specialty is farm-to-table systems design. She currently works at Round the Bend Farm in South Dartmouth.