Story and Photos By Christine Becker.

Winter’s drawn-out, ethereal sighs lull the cold earth into quietude. Resplendent with pale blue and silver-tinged mornings, the scent of damp pines, and the sound of icicles clinking outdoors, New Englanders savor the season with stick-to-the-bone chowders while hibernating under blankets of flannel. Yet by March, we find ourselves awaiting the emergence of bold colors and warmth on our skin—like delicate tendrils of fertile green, amidst sun-drenched skies and the purple crocus adorning the honeybee with boots of golden dust. Spring brings rejuvenation. As the gardener, with knees to earth, scoops up humus, inhaling its dark, sweet scent, the decomposition of summer’s fruits and autumn’s leaves by countless microbial colonies is immediately recognizable. A blank canvas, ready for edible and ornamental plantings.

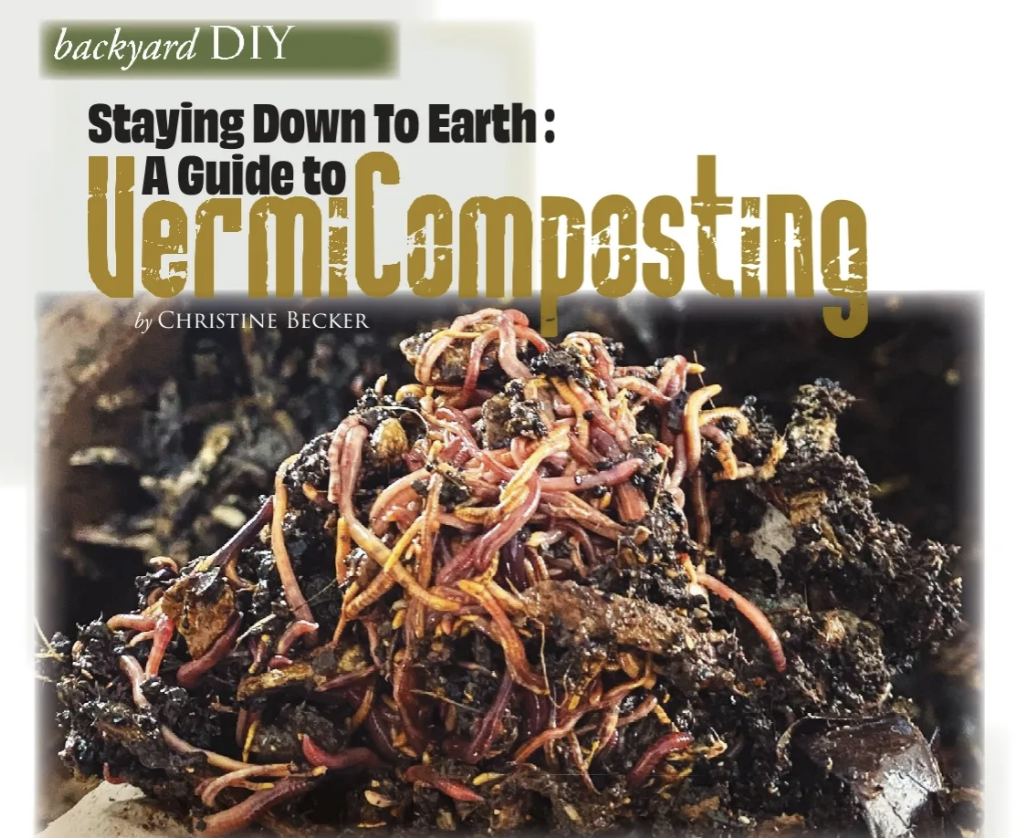

There is another organism, a little miracle worker, that produces a microbe-abundant and mineral-rich (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) compost to amend soil, proliferate the growth of plants, and create an idyllic growing environment for nutrient-dense herbs and veggies. Meet the red wiggler, Eisenia fetida in Latin, a composting worm with a reputation: notoriously low maintenance and able to tolerate a wide range of pH levels and temperatures. They tirelessly convert kitchen scraps to compost and could one day push synthetic fertilizers to the curb. Climate-friendly by nature, red wigglers reduce carbon and methane gas emissions by recycling trash that would normally be sent to landfill, including vegetable peelings, fruit cores, bruised fruit, eggshells, coffee grounds, and newspaper. Worm castings (worm poop) are high in organic matter and central to permaculture design and regenerative agriculture.

Individual interviews with three of the South Shore’s most experienced vermicomposters provide a comprehensive overview of this eco-sustaining craft.

Q: As we explore your worm compost operations, can you share how you first discovered vermicomposting and how long you’ve been doing it?

With a broad smile flanked by plastic red wigglers dangling from her ears, Janice guides me to a medium-plastic tub in her garage.

Janice McPhillips, Farm and School Garden Educator, Holly Hill Farm, Cohasset:

This is one of my vermicompost bins. About 15 years ago, I had difficulty accessing my backyard hot composting system (the bins were located behind snowbanks) when a friend told me I should explore vermicomposting, so I started! Worm castings—vermicast—are a higher-quality composition than what comes out of my hot composting bins.

As you can tell, I’ve put squash in here. Notice the remaining seeds and skins? And here’s an apple. About five years ago, I learned that the worms aren’t eating the scraps (like this apple), the decomposers—for instance fungi, mold, and bacteria—are eating the apple. The worms are eating the decomposers. Worms breathe through their skin and need moisture to survive, but you also need a lot of paper and carbon to absorb excess moisture. Otherwise, you’ll have worm soup! And since worms have gizzards to break down the organic material [Janice walks over to a bucket on her garage stairs], I crush up a handful of dried eggshells as grit to help them process the waste.

Eat My Garbage: How to Set Up and Maintain a Worm Composting System (35th Edition), by Mary Appelhof, is the lead manual for worm composting. Reading it, I learned some scientists have concluded that if you take eight worms and leave them alone for six months, you’ll have 1500 worms!

Waving me into his driveway with one hand in his pocket and cheeks rosy from the blistering morning air, Peter walks me through his front yard to his composting bin.

Peter Swanson, former AP Environmental Science Teacher at Quincy High School; President of Sustainability Project Honduras, LLC.:

I’ve lived in Hingham for 50 years and started a horticulture program for urban horticulture at Quincy High School, so I’ve been doing this for a while here. For 15 to 20 years, I used a turning compost bin, and about seven years ago, I came across Mel Bartholomew’s book Square Foot Gardening. It covers vermicomposting and square-foot gardening, a scientific method employing five types of compost to grow four lettuce plants, 16 radish seeds, and 12 beets in one square foot area. Janice McPhillips of Holly Hill Farm also introduced me to vermicomposting. I purchased my first batch of 20,000 red wigglers from Uncle Jim’s Worm Farm and have used them in an Earth Machine, an 80-gallon composting bin where food scraps and yard waste are decomposed by microbes and worms. It’s an easy starter. I have several different composters, but the Earth Machine [pointing to the one in his front yard] has become a resource for neighbors and people from around town who drop off their yard and food waste. But there’s one rule: No meat, no fat, no acid, no cooked foods—only veggie and fruit scraps.

In Honduras, I teach local growers how to compost, afford solar electricity, and construct kitchen gardens, and I also teach them the benefits of filtering water for drinking. It does no good to give a kid food if the water they’re drinking is full of parasites. I sell the Earth Machines to South Shore residents at $100 each—which supports my work there.

With a composed and gentle presence, Astrid ushers me into her garage as the late afternoon sun slipped into the horizon.

Astrid Peisch, President of the Community Garden Club of Cohasset:

I first heard about vermicomposting during the pandemic in 2020. I participated in a virtual walk-through at the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. They showed one horticultural staff member making compost tea inside huge barrels and explained that, while it fertilized the plants, it was also good for the environment. I thought, “that sounds like a great way to fertilize my garden organically!” I began the process by ordering supplies and ½ pound of worms from Uncle Jim’s Worm Farm—I’m about two years into the process!

[The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway is managed by the Greenway Conservancy, producing around 8,000 gallons of compost tea each year — 3,000 gallons are applied to their lawns and 5,000 gallons to their garden beds.]

I try to feed the worms once per week. I freeze all my kitchen scraps, including fruit that has gone bad and vegetable peelings. They don’t like anything spicy or acidic like citrus. Then I place it all in a blender, creating a thick smoothie which I pour onto one corner of the bin and top with coffee grounds and shredded newspaper or cardboard. I also rotate the feeding from left to right—that’s all it takes!

Q: Can you share with the readers why vermicomposting matters to you and to the community?

Janice: The EPA estimates that one-third of what goes into the trash is food waste and compostable paper—20% is food, and the other 10% is paper. If you’re worried about the negative effects of trash, this is a good entry point to do something positive about the environment. It’s very easy to make a huge impact on your waste.

Over the years, I’ve also learned that worm composting is a very easy thing—it’s much simpler than people may think. Worms (consider them as pets that work for you) create a high-quality product that enriches the soil in your gardens to grow healthy plants. I grow a lot of the food we eat from our home vegetable garden and a community garden plot. I also add the compost to my indoor plants, and in the winter, to herbs and potted kale by the windows.

Peter: Plants are beautiful, and they make you feel good. When you garden, we are using a range of motion beyond what you normally do, which is healthy. My wife has the most beautiful hydrangeas. People are always asking, “How did she do that?” It’s simple, I say! Just dig a hole, put compost in it, and because the soil becomes a culture of microorganisms—the perennials take off!

Many children and adults don’t really know where their food comes from, nor how it’s grown. We don’t understand how hard it would be to source food during a drought, how the extinction of foodsheds would impact many, especially the most vulnerable, and why we need to focus on saving our world—the planet’s ecological balance is out of order. But there are micro-solutions that are easy to implement: vermicomposting, composting, and container gardening systems, which can be used in urban spaces. Since urban homes can be so close together, there is little sunlight, but place a bucket rack on a patio or a driveway, and you can plant in planters. You place compost with soil and seeds and watch the plants take off! I also collect about 400 gallons of rainwater on my property, which I use to make worm tea.

Astrid: I live next to the ocean, and all the fertilizers treating lawns and gardens wash into the sea. The organic material in worm tea is much gentler on the environment, and things are growing in areas where there wasn’t much growth! There’s a lot of gratification to see the garden and lawn multiplying. I disperse most of my worm tea in the spring when it first warms up, but I will do another batch in the fall. I will fertilize the soil year-round inside my little hoop tunnel [a greenhouse structure where plants are in the ground].

[Astrid leads me to her worm tea bubbler, a 55-gallon plastic trash can with a small engine (fit for an aquarium) to keep the water circulated, as the bacteria need oxygen.]

My recipe includes tying a mesh bag full of 10 cups of worm castings, ½ cup of molasses, ½ cup of liquid kelp, and rainwater, and letting it bubble for 24 hours. If you must use chlorinated water from an outdoor water hose, add a teaspoon of vitamin C to counteract the chlorine (chlorine kills bacteria). You can also let the water bubble for a day to rid itself of the chlorine before adding the mesh bag. To get the beneficial, aerated microbes into the soil, make sure you use the tea as soon as possible.

Join in the Fun

If you’d like to join the vermicomposting community as a freshly minted composter or expand your existing composting skills, you are wholeheartedly invited to join in the fun, informative, and hands-on vermicomposting training at Holly Hill Farm in Cohasset. Find upcoming dates and sign up by visiting https://hollyhillfarm.org/events.