By Marek Kulig.

Pursuing oystering is more of a labor of love than a sole means of income.

Don Wilkinson sits on stacked oyster cages at the Plymouth Boatyard & Marina eating a slice of pizza. Around him, the Ichabod Flat Oysters team also relax and dig in. It’s about 2:30 pm on a mild, sunny and, most important, calm day in early March. They had just finished pulling boats up the ramp and backing them into their land berths when Don returned from picking up a late lunch.

“I’ll take weather like this every day,” says Sean Withington, punctuating his appeal with a bite of ‘za. Sean has been Don’s partner since the early 80s when the trade was mussels, and oyster growth in Plymouth Harbor was zilch. In addition to oystering, the two shared another working background as school counselors.

Though Don is now retired from school (Sean is not), he stresses that most oyster farmers have primary jobs, pursuing oystering more as a labor of love than a sole means of income, which is not to say that oystering is not profitable—because it can be, after a few years of investment. Lines of primary work of the Ichabod team include sales, carpentry, even funeral home directing. Others, like rockweed harvesters, are much more oyster-adjacent.

Oyster farmers, Don posits, “have a workaholic mindset.” Startup costs are heavy—the cages and crates, the boat. “All oystermen traditionally used Carolina skiffs,” Don says recently though, “We started using the front-loading aluminum boats built by [local boat-builder] John Boreland of Coastwise Marine. Now many oystermen are purchasing these crafts.” Don sings the praises of these locally-built, impressive vessels for their craftsmanship, sturdiness, and utility. And it is precisely this kind of talk, highlighting the applied talents and sustained efforts of those who innovate and toil to propel the industry forward, that showcases Don’s sincere, selfless enthusiasm for practicality and expertise. He’s a realist with a deep concern for the collective prosperity of his colleagues.

Startup costs are heavy—the cages and crates, the boat.

“Don cultivated the idea of reaching across the aisle to bring people together,” reflects Sean. As an example, Don’s ingenuity and ability to proactively connect with industry adjacent professionals led to the upgrade to John Boreland’s boats. To use a sports metaphor, he does the things that don’t always show on his own stat line but are crucial to the team stats. “We have a joke,” says Sean, “that Don may be technically challenged by a trailer hitch, but he can build a community.”

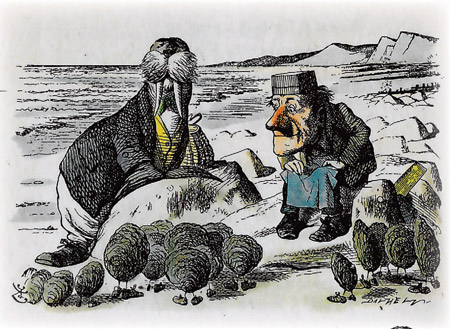

Decades of hardy, hands-on experience demystifies any fanciful notions of what’s involved with farming oysters, from the time they are the size of a flake of sea salt to when they mature into their craggy adult shells. Although you might suspect that oyster farming is rife with mystique and superstition, it’s really a very pragmatic business. Decisions are driven by tide charts and weather forecasts, wind and waves. Don does have a framed copy of Lewis Carroll’s beloved poem “The Walrus and the Carpenter” on his wall, but that curious tale of reckless young oysters who ignore the sage advice of an elder oyster and succumb to the dangerous enticements of a hungry walrus and carpenter bears no resemblance to the realities of oyster farming.

A scene from “The Walrus and the Carpenter” by Lewis Carroll, drawn by Sir John Tenniel in 1871, colored by Fritz Kredel.

John, one of the younger guys at Ichabod, proposes that culling and sorting oysters can be calming and can certainly have a meditative quality, “but when you’re out there in the middle of winter…” Don concedes that although this may be so, “after the 35th oyster, it’s labor.” The group nods.

None of this is to suggest a lack of levity on the part of the veteran oysterman. Don and his team share jokes and a camaraderie born of long hours working together and looking out for each other. Yet the labor is taxing; it’s in everyone’s best interest to be efficient. When asked if oysters could star in a less scaly and slippery role in a reality series like Wicked Tuna, where, say, competitive oysterers crunch numbers to determine whose harvest pumped clean the most water, Don says it won’t happen: “I think there is a lack of competition among the oyster farmers, and the tasks are all consuming.” In other words, don’t hold your breath for season one of Sedentary Oyster.

Don and his team share jokes and a camaraderie born of long hours working together and looking out for each other. All hands on deck at Ichabod Flats Oysters: Michael Withington, Jr., Sean Withington, Michael Withington, Sr., and John Cavicci.

The tasks are so physically consuming, in fact, that Don especially appreciates the simple things in life: his downtime with friends and family, relaxing and doing less strenuous chores, even frequenting the theatre (pre-Covid). Reading is a welcome respite, too. Don recommends Mark Kurlansky’s The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell. What Kurlansky learned from the research was that oysters were once considered a poor man’s food before becoming a delicacy for the upper classes. A similar change happened with mussels as Don knows from experience. They were considered “seagull food” by many, until the mid-1980s when there was a marketing campaign that made mussels a “white collar” treat.

Don recalls the changes he has seen in the oyster industry. “When we started, we were using hand rakes and handpicking off the bottom. Now we mostly use trays and boxed bags.” Name dropping, for lack of a better term, is to be expected from Don. But not in the self-aggrandizing sense, rather the opposite—to uplift and underscore the commitment and resilience of people who deserve recognition for their dedication to the industry. Don is quick to credit people well-known in the oyster world like Skip Bennett and Don Merry, and of course Sean Withington, as well as Michael Withington (and the aforementioned John Boreland!) for their time and tenacity and their nurturing of the evolving industry. Don himself finds purpose in striving for “the development of a quality brand of business. And there is always something to learn and experience. Seeing squid, squid eggs, finding eels, the occasional lobster, and various marine life mixed in with the oyster beds.”

“When we started, we were using hand rakes and handpicking off the bottom. Now we mostly use trays and boxed bags,” Don says.

Don also sees the importance of cultivating the interest of future generations in aquaculture. “I have one high school student (an employee) who is interested in a career on the water, and it is good to support him in his interests. Another former employee has gone on to work on a tugboat and attain his captain’s license.”

The impact of Don’s collaborative spirit and his invaluable tutelage has, over the span of almost four decades, shaped Plymouth Harbor into a stronghold of Northeast oyster farming. Who better to watch, listen, and learn from than Don Wilkinson, especially if the podium that day is a stack of oyster cages, and he offers you some ‘za.

Ichabod Flat Oysters

www.Facebook.com/IchabodFlat

The time has come,’ the Walrus said, To talk of many things: Of shoes — and ships — and sealing-wax — Of cabbages — and kings — And why the sea is boiling hot — And whether pigs have wings.’

Curious about the provenance of the name Ichabod Flats? So is Don. He’s offering a free tour of the oyster farm and fresh oysters to anyone who can uncover the origin.

Marek Kulig may write from Dartmouth, but he gets his oyster knowledge from Plymouth Harbor, where the water’s clean and the flats are tidy.