by Julia Powers.

For omnivores, there is a step from farm to table that is so difficult to consider, many choose to ignore it. Although we realize at some level that for us to eat meat an animal has to be slaughtered, most of us would rather the latter remain invisible. But if we are making thoughtful choices about our food, we should consider all aspects of the process, as difficult as they may be. If the ethical, humane treatment of animals during their life is a priority (and it should be!), then our concern should also extend to the animal’s final hours. A quality slaughterhouse will provide the same care and attention to the butchering of these animals, as the farmer did to raising them. And as much as we might wish to avoid thinking about the end of an animal’s life, the fact remains that if we want a local meat supply, we need local slaughterhouses, and in Massachusetts, slaughterhouses are in very short supply.

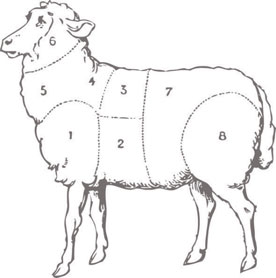

There are two types of slaughterhouses in Massachusetts—USDA inspected facilities, and custom exempt slaughterhouses. At the USDA inspected facilities, the USDA provides oversight on the processing of all meat that will be sold wholesale post-slaughter, to restaurants, distributors, or retail outlets (including farmers markets). To ensure all animals being processed are free from disease, handled humanely, and to ensure proper food safety is observed, all red meat (from cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep) must be processed in a facility that has continuous USDA observation. In Massachusetts, there are only two slaughterhouses with USDA inspectors—Blood Farm in Groton, and Adams Farm in Athol. Despite the word ‘farm’ in their names, these are processing facilities, not working farms, and they are critical to the availability of locally-raised meat. As Charlie Sayer, of Brimfield’s River Rock Farm notes, “We couldn’t do what we do without them. They are a vital cog in the wheel.”

Custom-exempt slaughterhouses, such as Den Besten Farm Custom Butchers in Bridgewater, can process animals that are for the exclusive use of the animals’ owners. This type of slaughterhouse is largely used by people who raise animals for their own consumption, or by anyone who purchases an animal from a farmer prior to slaughter—popular among many religious and ethnic groups who use these animals as part of their religious or holiday celebrations. While there are no USDA inspections at a custom slaughterhouse, they are subject to frequent inspections by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Products processed at this type of slaughterhouse cannot be sold either wholesale or through any retail outlets.

With only two USDA slaughterhouses in the state, there is not enough capacity to meet the needs of Massachusetts’ livestock farmers. In 2013, the situation was further exacerbated when a fire destroyed Blood Farm’s meat processing facility, temporarily taking them offline. Although they have since reopened, increased demand for locally-raised meat continues to strain the already limited capacity at slaughterhouses throughout the Commonwealth. At slaughterhouses, peak season runs from the fall through the holidays, and getting on the schedule during this time can be a challenge. Larger farms slaughter all year, but small farms do so in the fall because it is easier and less expensive to raise livestock during the spring and summer, making fall the busiest time of year. This can cause frustration, because farmers want to process their animals when they reach an optimum weight, but often face a long wait to secure a processing time, leaving them with two choices; they can drive their animals hundreds of miles to an out-of-state slaughterhouse, which stresses the animals and significantly adds to their costs; or they can continue to accrue additional costs for the animal’s care and maintenance as they wait for an opening at a closer-to-home slaughterhouse.

For farmers, slaughterhouses are a key part of the production process, but one that is beyond their control—and this can present certain challenges. For example, last fall, Brown Boar Farm, which raises heritage breed pigs and sells their meat at several South Shore farmers’ markets, faced a production backlog when the USDA inspector at their slaughterhouse left the job. Until a permanent replacement was hired, part-time inspectors filled in, keeping the facility running, but significantly slowing production. Although it impacted Brown Boar Farm’s product availability during a busy fall and holiday season, Meaghan Swetish of Brown Boar Farm remained philosophical, because whilst it did impact immediate supplies, she notes, “the USDA is a necessary part of the process to ensure a safe product, so in the long run it’s worth it because there is accountability for everyone.”

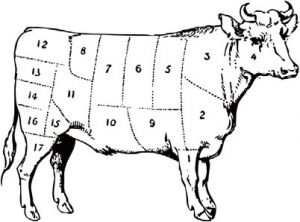

All farmers need to develop a good working relationship with their production partners, but this is especially true for farmers who raise their animals on pasture and incur extra costs to do so. Farmers want to know that their animals are being treated humanely and that the butchers give as much care and attention to how the meat is cut, as they have given to how it was raised. Ann Marie Bouthillette, who raises cattle and heritage breed pigs at Blackbird Farm in Smithfield, Rhode Island, notes, “When they (the animals) leave our farm, it is out of our control”, making the choice of slaughterhouse critical to the quality of the end product. As in any relationship, communication is key. Charlie Sayer has a good working relationship with the staff at Adams Farm and speaks with them frequently, “people want their steak cut a certain way—they are paying a lot of money for it” so he makes a point of talking to Noreen and Victor, owners of Adams Farm.

For many customers, one of the main reasons to buy locally-raised, pastured meat is the high quality of life these animals enjoy. Reflecting on this, Ann Marie Bouthillette, observes, “One of the reasons we are so meticulous with the last stages of life is that we work so hard to get (them) there.” So, for many farmers, the choice of slaughterhouse is driven by the desire to ensure that their own animal welfare standards continue through the end of life. The gold standard for animal welfare management is a process designed by Dr. Temple Grandin. Using Dr. Grandin’s humane handling methods, a slaughterhouse is designed with a series of one-way gates arranged in a circuitous path mirroring the animal’s natural pattern of movement. This substantially reduces stress on the animal which is important, not only for the animal’s welfare but also because stress hormones can negatively affect meat quality.

In Southeastern Massachusetts, a three-hour drive to have animals processed is impractical for small livestock farmers. In an innovative solution to this problem, the Southeastern Massachusetts Livestock Association (SEMALA) has begun the process of building a state-of-the-art, USDA-certified slaughtering and meat processing facility. According to Director Andy Burnes, the group has two parcels of land under agreement in Westport and is in the midst of the permitting process. The USDA awarded SEMALA a Local Food Promotion Program grant that has covered some of the initial expenses, and when completed, the facility will employ the highest animal welfare and food safety standards. With a total project cost of 4.3 million dollars, the group hopes to partner with a national organization to provide part of the funding, the rest of which will come from donations and bank loans. The group hopes to start construction by the end of 2015 and be operational by the following spring. Once completed, SEMALA plans to lease the slaughterhouse to a private operator. Initially, the facility will be able to process 1,750 large animals a year, but as Andy noted, “there is great interest and demand for local meat” so the facility is designed to double that capacity in subsequent years. There is great support for this project amongst both farmers and local food advocates.

Although slaughterhouses are an invisible part of the food supply chain, their role is instrumental in producing a quality end product. So, the next time you consider purchasing locally-raised meat, reach out to the farmer and ask questions. Ask how the animals lived—and the more difficult questions about how the slaughterhouse handled the end of the animal’s life. Knowing all the thoughtful choices your livestock farmer has made in raising and processing the animals, makes the decision to buy locally an easy one.

TLI

PO Box 879

Westport, MA 02790

Julia Powers is a writer, nutritionist, and cooking instructor who lives in Hingham. A firm believer in eating thoughtfully, most of the meat she cooks is pasture-raised, thanks to wonderful farmers and a well-stocked freezer!