Whale Fever

By Paula Marcoux

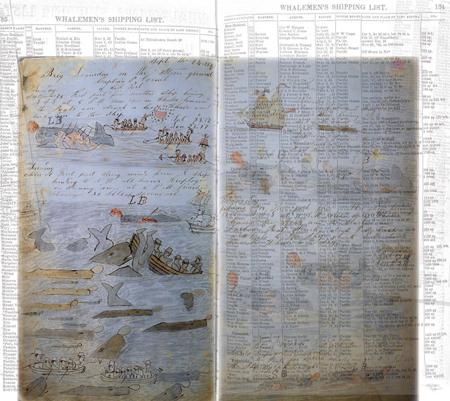

Recently, laid low by an upper respiratory infection, I spent a couple days peering through an online window in time called The Whaleman’s Shipping List & Merchant’s Transcript. With “a circulation extend(ing) to London, Dublin, Glasgow, Canary Islands, Paris, China, St. Helena, Barbadoes (sic), New Zealand, Chili, Tasmania, Berlin, Azores, etc.”, this weekly broadsheet ran from 1843 to 1914, capturing the blazing apogee of the whaling trade, and then its long decades of decline. Described in 1883 as “the only paper of its kind in the world,” the List & Transcript was not merely a compendium of commodity prices, notices, and ads, but it was also a wikitrove of critical intelligence of a sort that had previously been gathered and disseminated piecemeal by the whalers themselves, as well as by industry friends and family. The key data points? The last known location, condition, and cargo of every single American whaleship afloat.

From its earliest years in the Old Commercial Bank building on New Bedford’s North Water Street, (fittingly fated to become the core of the New Bedford Whaling Museum), The Whaleman’s Shipping List & Merchant’s Transcript chronicled the industry at its epicenter. In the late 1840s, New Bedford was a sparkling, brand-new town, buoyed on a king-tide of pure cash rendered from the blubber of the whales that its captains circled the seas to slaughter. But it did not tip its hand to the visitor as an obvious boomtown. In the words of an experienced seaman who shipped out on a whaler in 1850 (just three years after New Bedford incorporated as a city) the place was, considering the immensity of the business based there, remarkably “still”:

A more quiet and rural looking place than that portion of the city beyond the immediate business limits, it would be difficult to imagine. And a more beautifully laid out or better-kept city I never saw. It was now mid-summer and the spacious mansions embowered in green foliage, which border the principal streets, looked really enchanting to my eyes, long wearied with monotonous salt water views; while a walk up the well-shaded streets was like a trip into the country. New Bedford well deserves the name of being one of the most beautiful cities in New England.

Hard by those shady avenues, the labor of an immense and diverse army of workers filtered through the wharves and counting-houses ranged along the Acushnet River. But the Shipping List reveals how the scene retained its placid appearance through all of this fevered money-making: of the hundreds of whaleships based in the town, only a couple dozen were present in port at a time, disgorging their contents or refitting or provisioning for the next voyage. Ninety percent of the fleet was working distant seas, almost never touching land, commonly absent from the home-port for four years at a stretch. And the work of laying up rope, sawing timbers, sewing sails, underwriting insurance, baking ship biscuit, copying ledgers, salting beef, raising superfluous farm boys to become greenhands—all of these things could be carried on under cover in disparate production loci.

The actual work of harvesting whale oil, too, was prosecuted remotely on a truly global scale—from the Bering Straits to the backside of Madagascar to the most removed islands of Fiji and Crozet. The countless thousands of whales killed had themselves likewise cruised the seas accumulating all that desirable adipose tissue, metabolizing the purest of fats from untold trillions of krill and squid. If you picture the entire business as a sandglass, with the whales scattered all over the seas of the world contained in one glass, and the consumers lighting their homes all over the United States in the other glass, the town of New Bedford was that tiny thread-bound waist of the glass, the still center funneling all that energy, all that wealth, from one world into the other.

As someone very interested in the provisioning of ships through history, I half-expected that these ingenious and single-minded Yankees would have invented a novel system to feed a more or less hermetically sealed population of forty men for four years, as they alternated between laying idle and working like dogs in every earthly latitude. But their sea diet in most respects closely resembled that of Europeans on sixteenth-century voyages: salt beef and salt pork and hard biscuit, pre-fab foods prepared by professional provisioners. Engineered to be durable and calculated to portion, barring disasters and cheats. Like the majority of the ships’ crews, the food they were to eat at sea came from the farms of the Genesee and Ohio and then Mississippi Valleys. Raised, processed, and barreled, then freighted by canal and riverboat.

Fresh meat and novelty might occasionally be had in the form of whale steaks and other occupational windfalls. (Including, in one account, an unlucky hippo harpooned and butchered by whalers gone to fetch firewood from the South African shore.)

Canny skippers knew how critical fresh anti-scorbutic foods were to the health of the crew, and did their best to find supplies. An outbound stop at the Azores might bring in a load of citrus, at Tristan da Cunha a boatload of potatoes. One account by a whaling hand describes a practice particular to whalers, a manner of dividing the spoils of the captain’s citrus purchase:

When the anchor was stowed and all snug for sea, the oranges which had been brought on board were divided among the crew, each one receiving a share to take care of, and eat as he saw it. This is the usual manner of proceeding in such cases, on board a whaleship, and prevents all after quarrels, inasmuch as each one can make as much of his hoard as he pleases.

My share amounted to nearly three hundred. They lasted three weeks, and it was with an anxious desire for more that I put the last and juiciest one to my lips—well knowing that many months would, in all probability, elapse before we should be favored with another run into port.

(Inspired by these men, and in honor of my cold virus—and in the spirit of experimental archaeology that so often moves me—I put down my book and straightaway attempted to eat fifteen oranges.)

The final years of The Shipping List document a business in irrevocable decline, doubtless still turning a dollar for banks, insurers, and other sorts of profiteering middlemen, even as the industry slid back to zero. (Literally. The paper reported in its final 1914 edition that ships had returned from multi-year voyages with not one whale.) But the story is full of fascinating vicissitudes along the way—extraordinary and singular disasters like the Arctic torching of dozens of New Bedford vessels by Captain James Waddell, the dastardly commander of the Confederate steamship Shenandoah, in June of 1865, after the Civil War had officially ended. (Waddell dismissed as a Yankee lie the news that hostilities had ceased, but was able to believe that President Lincoln had been assassinated because he expected that he had it coming…) Or the epic over-ice trek by the crews of 33 whaleships trapped and crushed by massive gale-driven icebergs in September 1871. Because the business was structured so as to spread out risks, most investors were well-padded enough to withstand those kinds of losses—the smart local money had long diversified into textile manufacturing anyway.

Protracted as it was in finally coming, the snuffing out of the whaling industry was of course inevitable. America’s new source of light and heat, “rock-oil”, was being harvested from subterranean crannies beneath Pennsylvania, a distillation of residues from creatures even older and more terrifying than Leviathan. Oh, and weren’t those crafty cetaceans getting better and better at hiding themselves from the poor whalemen! Accounts advising how the wily whales seem to have left this or that fishing ground out of cunning and cussedness scarcely ever breathe a note of awareness that there might be such a thing as extinction.

Resources

Get up your own expedition to learn about this sobering slice of local/global history. Provision your voyage by planning lunch at one of New Bedford’s great restaurants.

Visit:

New Bedford Whaling Museum

18 Johnny Cake Hill

New Bedford, MA 02740

(508) 997-0046

www.WhalingMuseum.org

New Bedford Whaling National Historic Park

33 William Street

New Bedford, MA 02740

(508) 996-4095

www.NPS.gov/nebe

Or . . . stay home and read:

https://research.mysticseaport.org/reference/whalemens-shipping-list/ Whaling and Fishing, by Charles Nordhoff (wonderful; available on Google Books)

Acknowledgements:

Historical New Bedford whaling images and lists provided by New Bedford Whaling Museum (in coordination with Mystic Seaport).

Paula Marcoux is a Plymouth-based food historian and the author of Cooking with Fire. Doughnuts fried in a try-pot is at the top of her Historic-Foods-I’ll-Never-Get-To-Make list.