This is the first of three articles chronicling the Town of Duxbury’s acquisition and preservation of a piece of land for agriculture and the start-up of Fowl Play Farm.

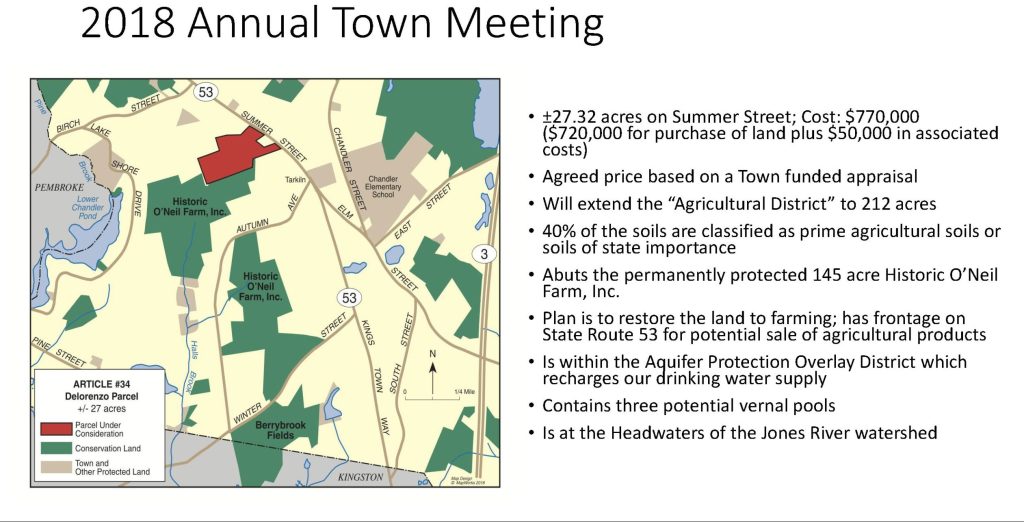

Recognizing the importance of agriculture and locally grown food, in 2018 the residents of Duxbury purchased a property once known as the DeLorenzo Farm, a 27.32-acre parcel that was a turkey farm until the late 1950s. It took a couple of years to purchase the land, select a farmer, clear the land, install wells, and make other improvements to prepare the property for farming, and by 2021 these steps were complete. That seems pretty fast for this sort of project—but actually, the project was decades in the making, completed with the cooperation of a farm-minded landowner and thanks to the hard work of dedicated town employees and residents. Of course, whether it would succeed was a whole other question, for as any farmer will tell you, farming is a risky proposition and getting a new venture started is riskier still.

Farm to Farm

Linda DeLorenzo’s grandparents immigrated from Selena, an island off the coast of Sicily, around 1911. Her grandfather had been a farmer in Italy. He bought a farm in Duxbury, and with the help of his two sons, continued farming in his new hometown. Linda recalls the rows and rows of vegetables—tomatoes, squash, peppers. They kept bees to pollinate the gardens, the hives housed in little huts with peaked roofs. When she was very young, Linda was not allowed in the working gardens—think bees and the kinds of mess kids can make.

By the late 1940s, the focus shifted to turkeys. It was a pretty big operation for its time. “We’d get between 7,000 and 9,000 day-old turkeys in the spring,” Linda recalls. The DeLorenzos raised the poults through the summer and sold them in the fall. “I remember opening day was a big day. My mother would make turkey sandwiches for the people who came to buy their turkeys. My father would tell people how to cook them for Thanksgiving. I remember a lot of people didn’t know how to do it. Eventually, my father started cooking them for people, roasting them, and barbecuing.”

Linda’s father attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts, Amherst), but much of what he learned came from working with other farmers and benefiting from resources offered by the state. “There were several farms raising turkeys in Southeast Massachusetts—Middleboro, Marshfield—and the farmers would get together periodically to share stories of what worked and what didn’t. The head of the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture also came to the farm to give advice. I do not remember much about the meetings except that they usually ended with a poker game. I remember sitting on my father’s lap while they played cards. It was a nice group of men.”

The turkey business continued through the 1970s, at which point Linda’s parents retired and farming took a pause. Duxbury was changing as well. House lots are now wrapped around two sides of the property. By 2000 Linda was receiving calls from developers who eyed the property for another residential development, but she turned them down. Linda knew she wanted to keep the land in agriculture.

Proactive Protection

Proactive Protection

Simultaneously, a small group of Duxbury residents and town officials started discussing ways to preserve the town’s rural vistas and its agricultural past. They identified parcels for preservation and acquisition and noodled how best to approach landowners. Joe Grady, recently retired from his career as the town’s Conservation Agent and long involved in the town’s land acquisition program, says, “We started meeting informally, identifying key parcels.” Pat Loring, also a long-time land conservation expert, echoed the memory. “We identified parcels within three corridors in town. The DeLorenzo property is right along the Western Greenbelt and it became a priority.” They started talking seriously with Linda in 2008.

On open space protection, Pat says, “Protection of our local land is important. Open space in general is important for the character of a town, and I think it’s necessary to balance growth with the need to preserve open space. The conserved land should add important values to a town: habitat values, recreational values, agricultural values.”

Asked why the DeLorenzo property, in particular, is important, Loring and Grady also saw synergies with other agricultural properties in the area, citing the abutting Historic O’Neil Farm, a dairy farm that has been operating continuously for over a century, conserved in 2005, which also sits in the Western Greenbelt. They see the DeLorenzo property as an anchor with frontage on a major thoroughfare (Summer Street/Route 53). “You have to envision 50 years from now what it could be, which we cannot really imagine now. The anchor the DeLorenzo property provides with the O’Neil Farm and the Berrybrook Fields builds an agricultural corridor in West Duxbury of nearly 215 acres. That is huge,” says Loring.

As purchasing the DeLorenzo property started looking like it might actually happen, Loring, Grady, and a few others looked to other town-owned farm properties to see what they could learn. Examples included the Soule Homestead Educational Center in Middleboro, the Jacobs Farm in Norwell, and several farm properties in Concord and Lincoln, Massachusetts. They learned from all, but the Soule Homestead proved to be where they learned the most, with its chicken tractors, pigs in the woods, sheep, crops, and multiple farmer tenants to manage.

Loring and Grady learned that you have to have the land ready for a farmer but you cannot micromanage the farmer. “You have to provide the infrastructure,” says Grady, “there has to be water and you have to do some clearing and you have to be ready to help the farmer get started, but you cannot be the farmer.”

Loring agrees, citing the town’s involvement in building the infrastructure by drilling two wells, installing gates at entrances to limit unauthorized access, and constructing a perimeter fence. But they learned that you also have to listen to the farmer. At first, the group planned to clear several acres to establish a large open field. But after a discussion with a prospective farmer, they decided to slow down. “You have to work with the farmer,” says Grady. “We realized [the farmer’s] idea to incorporate silvopasture (retaining woodland), would be a much better way to return the land to agriculture.”

Grady and Loring also learned that the town has to get out of the way. “You have to be very generous with letting the farmer farm. You cannot tangle them up with rules and procedures.” Grady recalls incidents where well-intentioned towns required farmers to adhere to practices that became unwieldy. “In other communities [the towns] have made crazy requirements like the police being notified when pesticides are sprayed; horns going off and whistles going off and flags are raised when pesticides are being used, and the farmers just walk away. It becomes too much.”

Back to Life

Ultimately, the town issued a Request for Proposals, and Brett Sovick of Fowl Play Farm responded. Sovick, a Duxbury resident, had been a hobby farmer (maybe more a gardener) for decades, but during Covid, he got more serious. His 1.3-acre residential property hosts pens for chickens, ducks, and quail. He sells both meat and eggs from the birds. And there is room left over for a vegetable garden and two beehives.

As for many, his wake-up call came after watching Food, Inc., a movie about industrial food production. He did a little arm-chair research and realized, “Oh my God. This is a major problem. The industrial ag complex is annihilating our food on so many levels.” And so he read more, becoming a bit of a disciple of Joel Salatin, a farm activist featured in Food, Inc. “Being able to provide for yourself and your family and your neighbors, it is very, very important… We need to do better.”

Sovick’s five-year plan is ambitious and includes plans for raising pigs and cows for meat, chicken tractors, rows and rows of vegetables, and maybe an orchard. He also has plans for involving the community by including volunteers, teaching classes, collaborating with other interested farmers, and working with entrepreneurs to develop value-added products. But his expectations are tempered by the recognition that things may take a while. “It takes time to get established. It is not turnkey up and running, it is a process, but once you get that process started it is a tsunami.”

Loring and Grady are optimistic. “[Brett] knows the people at SEMAP, and he is in the loop of Southeastern Massachusetts agriculture. I think his plan is good and he seems in it for the long haul,” says Loring. Linda DeLorenzo agrees. “The land is beautiful and the soil is good. He seems energetic and enthusiastic. Farming requires time and planning and a farmer who is patient.”

Time will tell, and we’re rooting for Brett’s success.

Sam Butcher is a Duxbury resident and member of the town’s Conservation Commission. He is also involved with the Historic O’Neil Farm, another farm located in Duxbury.