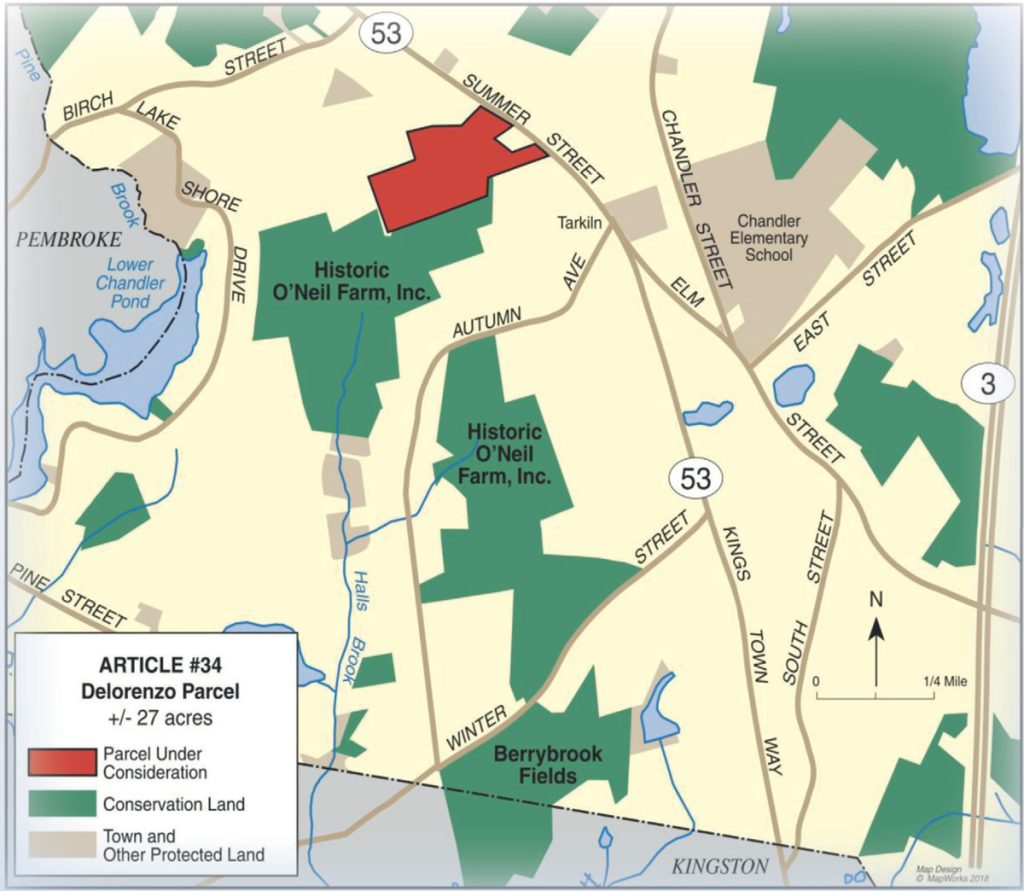

Recognizing the importance of agriculture and locally grown food, in 2018 the residents of Duxbury purchased a property once known as the DeLorenzo Farm, a 27.32-acre parcel that was a turkey farm until the late 1950s. It took a couple of years to purchase the land, select a farmer, clear the land, install wells, and make other improvements to prepare the property for farming, and by 2021 these steps were complete. That seems pretty fast for this sort of project—but actually, the project was decades in the making, completed with the cooperation of a farm-minded landowner and thanks to the hard work of dedicated town employees and residents. Of course, whether it would succeed was a whole other question, for as any farmer will tell you, farming is a risky proposition, and getting a new venture started is riskier still.

This is the second of three articles chronicling the Town of Duxbury’s acquisition and preservation of a piece of land for agriculture and the start-up of Brett Sovick’s Farm.

If you are going to ask Brett Sovick what his plans are for the DeLorenzo Farm, his vision for the rebirth of a farm dormant and abandoned for decades, you’d better set aside some time for his response. You might also want to brush up on your knowledge of alternative forms of agriculture. He’s got lots of ideas, including a few you may not have heard of, and he is happy to share them.

Brett recently signed a ten-year lease with the Town of Duxbury to be the tenant farmer on a 27-acre property known as the DeLorenzo parcel. In the 1950s it was known as the DeLorenzo Farm. Though once a prosperous vegetable and later a turkey farm, until recently the significant majority of the property was overgrown and wooded, with a few small wetland areas and a small area of open hayfield, used by a neighboring dairy farmer. But Brett is breathing new life into the property and, with some assistance from the town, is making fast progress at returning the property to agriculture. His vision is for a regenerative and community-based farm where people can learn where food comes from and buy food that is locally grown.

HATCHING A PLAN

Beehives at the farm should benefit both the crops at the farm and those on neighboring properties.

Brett had an epiphany several years ago, one that you too may have had after watching Food Inc., the movie about industrial agriculture and food production: There is something wrong with how we get our food. He started reading and became a disciple of Joel Salatin, a farmer and advocate for innovative, sustainable agriculture. He took courses and read some more. He expanded his little backyard garden. He added bees and then chickens, the “gateway livestock” as he calls them, and then ducks and quail. Honey, vegetables, meat (the chickens), and eggs (chickens, ducks, and quail). Though he wanted to do more, he ran out of room on his 1.2-acre lot, so he took a leap of faith and responded to the Town’s Request for Proposals, presented a five-year plan, and found himself the proud ten-year tenant of the DeLorenzo Farm.

Brett plans to actively farm about ten acres of the 27-acre parcel, leaving an extensive woodland buffer between his operations and abutting residential properties as well as leaving buffers around several interior wetlands. But those ten acres…they will be used intensively.

Brett expanded an already open area to accommodate two or three acres that he will use to grow produce. In this area, he is layering wood chips (carbon) and rotted silage hay (nitrogen) that he will lightly till into the soil to create a nutrient-rich “carbon bomb” that he hopes will give a boost to the already superior agricultural soils. He is creating three roughly 100-square-foot test plots, each of which will have 15 to 20 beds with three or four rows apiece. In early spring 2023 he planted several rows of garlic as a test crop. The garlic worked well enough that he planted squash, tomatoes, and other vegetables as the weather warmed.

PERMACULTURE IN ACTION

German technique Hügelkultur

Ever the experimenter, Brett constructed a modest Hugel Mound on a portion of the property where he thinks he may be able to grow vegetables more intensively. Hugel Mounds, garden beds built using the German technique Hügelkultur, are small mounds constructed with a core of decaying wood debris, covered by dead leaves and soil, covered by partially decomposed compost, and topped with a layer of finished compost and soil. Permaculture enthusiasts have embraced Hügelkultur and the technique is increasingly popular in the U.S. Hugel Mounds are thought to increase soil fertility and water retention. Further, because the surface area of the mound is greater than the surface area of its footprint, Brett believes he will be able to plant crops more densely on the mounds. A small test plot with squash supports this idea.

The creation of silvopastures requires the creation of pastures in wooded areas. Here an articulated implement is used to carefully remove deadfall from among trees.

Brett is creating four or five acres of silvopasture in the wooded areas surrounding the fields of produce. Silvopastures integrate trees, forage, and the grazing habits of domesticated animals in a mutually beneficial way. If done right, silvopastures increase overall productivity due to the simultaneous generation of trees and livestock. Silvopastures also maintain wooded habitats for species already in the area. Using low-intensity and low-impact equipment, Brett is removing the deadfall and thinning the tree canopy. Once removed, the larger trees will be milled into lumber to be used in the construction of barns and sheds. Smaller logs will be used as fence posts around the farm’s perimeter and around the produce fields. Smaller branches and trees that cannot be otherwise reused will be chipped for bedding or on the fields as a carbon source.

Once the woods are thinned Brett plans to rotate chickens and ducks through the silvopasture space, as well as sheep, goats, pigs, and possibly beef, with a series of small portable paddocks. This will allow him to carefully manage the livestock, while also allowing the fallow pastures to recover.

Brett also plans to have three or four chicken tractors that he will move across a couple of acres of field currently used by a neighboring farmer for hay production. “I plan to work with the farmer so that we can both benefit,” says Brett. According to Brett, tests have shown that the hayfield is lacking in certain nutrients. He believes that moving chickens across the field will increase the nutrients on the field. “I want to work with the farmer as best I can. Working around his haying schedule. The nutrients that the chickens leave should give a boost to hay production for the next cutting.”

PLANTING SEEDS IN THE COMMUNITY

But it does not stop there. Brett is already planning classes on how to raise and process backyard chickens. He also intends to hold classes on gardening, animal husbandry, how to pickle eggs—the list goes on. “I want people to be able to get onto the farm. I want them to be able to touch and smell things. I want them to fill their senses as to what a farm is supposed to be like.”

I asked Brett what his motivation was for taking on the challenge of starting a small farm, for doing all this. “I want people to know that we do not have to accept industrial agriculture. I want people to know where their food can come from. I value food security and I want to be able to produce food for myself and for others. Thomas Jefferson envisioned a nation of small farms where farmers feed communities. We have gotten too far from both small farms and from community. We can do better.”

Sam Butcher lives in Duxbury, is on the town’s Conservation Commission, and is also involved in the Historic O’Neil Farm.