By Paula Marcoux.

Today, the majority of Americans may be found cooking and celebrating in certain familiar ways when Thanksgiving and Christmas roll around. But not so long ago, the landscape of winter holidays in New England laid out a very different scene and a pretty unfamiliar table. Back in the early 19th Century, once the last of Thanksgiving’s chicken pie, mincemeat, and plum pudding had been eaten, patriotic New Englanders looked forward to a steaming pot of old-fashioned succotash on December 22nd—Forefathers Day—to bring the winter holiday season to a close. It was not Thanksgiving but Forefathers Day—alias Old Colony Day—which bore the symbolic weight of the legend of “the Pilgrims,” according to James W. Baker in Thanksgiving: The Biography of an American Holiday. And while the Thanksgiving menu featured a panoply of rich dishes signifying abundance at harvest time, Forefathers Day focused on a single, humble, homespun dish. Old Colony Succotash was identified with a seemingly simpler bygone era for which nostalgic New Englanders yearned as they struggled through tumultuous, uncertain decades from the run-up to the American Revolution through the economic and political mosh-pit of the 19th Century.

By the wrenching close of the Civil War, Thanksgiving had become a truly national holiday, inheriting the nostalgic burden of Forefathers Day, even while eclipsing it. The last nail in the coffin for good old Forefathers Day came by the start of the 20th Century, with the acquiescence of New Englanders to the formerly unthinkable celebration of Christmas; today the stalwarts of Plymouth’s Old Colony Club are among the last few succotash-eaters on December 22nd.

To a modern cook, the recipe is forbiddingly stodgy-looking; but when one has spent the morning of a frosty December 22nd dragging the top half of Plymouth Rock up to the Liberty Pole or tarring and feathering the Tory neighbors, it’s just the thing.

Cook’s Notes: The explicit timing of this recipe assumes you are eating your succotash as the noontime mid-day meal. Halving the original recipe makes a vast amount for most applications. The beans are of course dry and the hulled corn is dry hominy, which takes a little work to acquire; check the Hispanic section of the grocery store and substitute canned hominy, if that’s what you can find. Taste for salt as you add the vegetables and correct the seasoning.

Thanks to author James W. Baker for this nineteenth-century recipe, which is so clearly-written it scarcely needs explication:

“Mrs. Barnabas Churchill’s Succotash”

1 quart large white beans

6 quarts hulled corn

6 – 8 lb. corned beef

1 lb. salt pork

4 – 6 lb chicken

1 large French white turnip

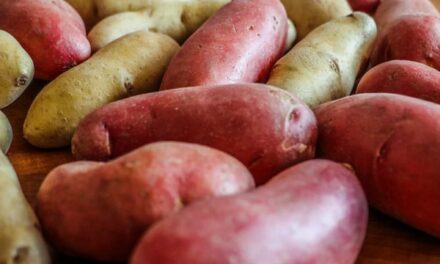

8 – 10 medium sized potatoes.

Soak beans overnight. In the morning simmer in soft water until beans are soft enough to mash and water is nearly absorbed.

At about 8 am, put salt pork and corned beef into a very large kettle of cold water. Skim as they begin to boil.

Two hours before dinner time put mashed beans and hulled corn into kettle with some of the fat from the meat to keep them from sticking. Add enough liquor [stock] from the meat so that the mixture will absorb it all but not be too dry.

Clean and truss chicken and add to kettle of meat about 1¼ hours before dinner time. Allow longer if fowl is used. Be sure to have plenty of water in kettle.

Cut turnip into inch slices, add to meat about eleven o’clock. Add potatoes, one half hour later. Remove chicken when tender and serve whole. Serve beef and pork together, the chicken, turnip, and potatoes in separate dishes, – the beans and corn in the Succotash Bowl. The meat generally salts the mixture enough. Save the liquor from the meat to warm the corn and beans the next day, serving the meat cold. Like many other dishes, this is better warmed over.”